This is the first article in a three-part series looking at the rise of SNAP online purchasing.

For over a year, Walmart and Amazon have dominated SNAP online purchasing, expanding the offering from New York in April 2019 to now nearly every state. But that is poised to change as hundreds of grocers this year look to allow shoppers to pay for online orders with their Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) cards.

"It's something that we're hearing from every retailer pretty much that we work with. They want to be able to move forward with it and offer it," said Jeremy Neren, co-founder and CEO of GrocerKey, a white-label e-commerce technology provider.

When the coronavirus pandemic hit the U.S. last spring, the U.S. Department of Agriculture's (USDA) Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) opened up applications to its SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot, which previously featured a few retailers chosen by the government.

Since then, approximately 300 retailers have sent in letters of intent expressing interest in joining the pilot, a spokesperson for the USDA wrote in an email. A "couple hundred" retailers are expected to go live by the end of the year, said Brad Goad, vice president of digital commerce solutions at Fiserv, the financial services technology company partnered with the USDA.

"We expect to have somewhere between 2.5 to four times as many merchants live by April as we do now," Goad said in late January.

For now, shoppers in most states face limited options. Only 11 of the 46 states that have gone live with the pilot have at least one grocery banner participating that isn't Aldi, Amazon or Walmart.

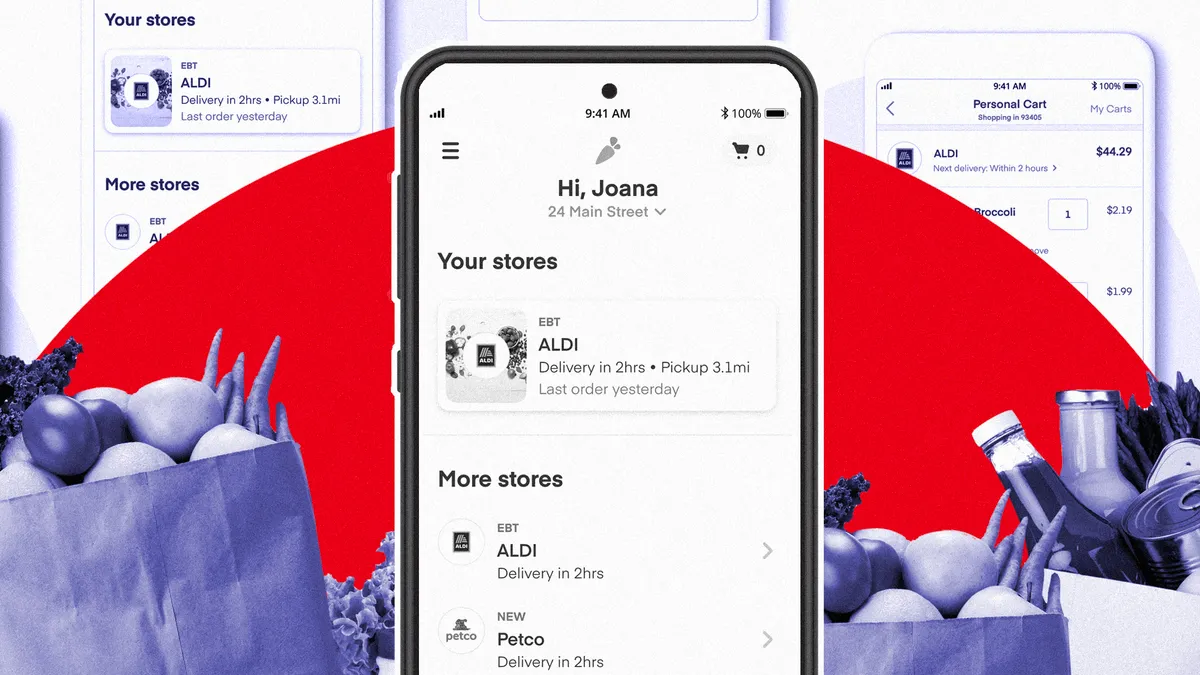

Aldi, which started rolling out SNAP online purchasing with Instacart in late 2020, expanded the capability quickly to stores across its footprint in 37 states and D.C.

While shoppers wait for more options, grocers and e-commerce providers are working on SNAP online purchasing behind the scenes. Instacart has "begun the process to onboard additional retailers," Andrew Nodes, vice president of retail at Instacart, wrote in an email. Last week, Food Lion started accepting online EBT payments through Instacart in North Carolina, with plans to expand the offering to eight more states in the coming weeks, according to Instacart.

Meanwhile, Hy-Vee, which currently lets customers pay with their EBT card at pickup, has a multi-phase process underway. Currently, it's rolling out its SNAP/EBT ordering platform and will then offer EBT online payment for pickup orders, followed by grocery delivery, a spokesperson for the Midwest grocer wrote in an email. Albertsons has started efforts to offer SNAP online purchasing in Washington, and a spokesperson for the retailer said the grocer is working with the USDA to bring the option to additional locations.

Up until this point, many retailers like Kroger and Albertsons have offered a stopgap where SNAP recipients can place online orders, but have to pay with their EBT cards when they pick up their purchase. Sources told Grocery Dive that eliminating that extra step and providing more choices is important.

"We like to give the SNAP customer all the same opportunities as other customers. … That's important, both in terms of them feeling comfortable and not stigmatized, but being able to do things and be treated normally in a mainstream way," said Ellen Vollinger, legal director at the Food Research & Action Center, a nonprofit focused on poverty and hunger advocacy.

SNAP can be lucrative for some grocers, and the online purchasing component is another way to reach the rising number of SNAP recipients. As of September 2020, roughly 42.9 million people received SNAP benefits, with an average benefit of $183.54 — compared to 37.6 million SNAP recipients with an average benefit of $120.52 in September 2019, according to data from the USDA.

Going from "zero to 100"

Shoppers and advocacy groups have questioned why more grocers aren't offering SNAP online purchasing as the USDA approves dozens of states for the pilot.

In February 2020, the pilot had two approved states and three retailers, but now it has 12 retailers across 46 states and Washington, D.C. Maine received USDA approval in December for the pilot but has not gone live yet.

"We've only seen one new retailer get set up in New York state since the pandemic began and there really has been such an outcry of demand for an expansion of SNAP online, because there's only four retailers in the state," said Sherry Tomasky, director of communications and public affairs at Hunger Solutions New York. Tomasky noted that those retailers — Amazon, Walmart, ShopRite and Aldi — "only participate in some parts of the state and not others."

Cameron Market in Missouri has received "numerous" questions about online SNAP payments ever since the state was approved last spring, owner Tony Clark wrote in an email. "Meanwhile, all customers know is supposedly they can use their benefits online, and we are telling them that we cannot process them," Clark said. "It is difficult to communicate to them all that has to happen to make this a reality."

"The challenges really have been about going from zero to 100 in a very short period of time."

Brad Goad

Vice president of digital commerce solutions, Fiserv

As states and retailers seek approval from the USDA to join the pilot, the pipeline has gotten clogged, with sources pointing to volume overload, having one payment processing partner working with the USDA and retailers, and technology vendors figuring out the complex process.

Vollinger said that while "sometimes people just assume it's a lack of will at USDA or it's a lack of will on the part of some piece of this puzzle," the government and the grocery industry have been working on and prioritizing SNAP online purchasing for years. "The journey for SNAP and technology has been one that's usually quite incremental," she said.

Some sources were quick to praise the federal government's efforts to expand the pilot during the pandemic and to make the process easier and faster.

"It is clear that [FNS staff] are working as hard and as efficiently as they are able to, despite the program expanding much more quickly than anyone anticipated," Molly Pfaffenroth, senior director of government relations at the National Grocers Association (NGA), wrote in an email. "The pilot program took several years to set up and was just off the ground when the pandemic hit."

However, grocers and tech vendors said they faced frustrating delays, which sometimes hurt their bottom line. Cameron Market started working with its e-commerce provider Freshop last May and, nine months later, is about to start one of the final steps toward going live, Clark said. The wait has placed his store "at a severe competitive disadvantage because Walmart was in [the USDA's] initial pilot program."

Goad of Fiserv said the backlog was largely due to the "massive amount of integration work and go lives with the state issuers over the last year and getting through the contracting process." Those delays have been largely resolved, he said.

"The challenges really have been about going from zero to 100 in a very short period of time, and just handling the mass influx of demand from merchants to offer this and then maturing the contracting, the review, the implementation process and understanding with FNS what's working, what's not," Goad said.

Even with the backlog, Pfaffenroth said there has been significant progress with FNS and Fiserv, pointing to several independent grocers, including Woods Supermarket in Missouri and Carlie C’s IGA in North Carolina, that went live in late 2020.

Goad said the process is moving "much faster" now, noting that FNS does not want to sacrifice protocol or requirements because of concerns about security and fraud issues. So far, fraud has been a “non-issue," he said.

Going forward, grocers may have a quicker experience setting up and getting governmental approval for SNAP online payments when working with a technology provider that has already gone through the process and made its SNAP e-commerce solutions repeatable and scalable. Smaller and mid-sized grocers with limited resources may want to specifically partner with e-commerce providers to help them take on the financial, logistical and technological challenges of offering online EBT payments.

Complexities create confusion, costs and delays

The federal government set up requirements for the pilot that is then administered by the states. The tech powering the EBT e-commerce experience also has to meet certain federal and state requirements.

The process involves multiple steps, starting with a list of eligibility requirements and ending with FNS testing of the SNAP online purchasing experience. "Ultimately, the timing is at the discretion of the retailer, as many complete these steps in varying order," a USDA spokesperson said.

Sylvain Perrier, president and CEO of grocery e-commerce platform Mercatus, said that delays stemmed from waiting for Fiserv and the USDA to scale their operations "and then, equally, all of the service providers have to follow suit and scale as well."

Perrier said that Mercatus has not faced delays with the process, but that its retail partners will. "[The] certification process — that list is very long from my understanding," Perrier said.

Grocers and tech firms say the process could be fine-tuned to remove obstacles, especially for small and mid-sized retailers that often have fewer resources and more financial constraints than larger ones.

Several grocers and tech vendors said they don't understand why offering SNAP in-store and online hasn't been streamlined, at least partly, into one process. For example, when retailers get certified for SNAP in-store, they receive a retailer identification number from FNS, and then get a separate identification number when they look to also offer SNAP online.

"I believe using the same FNS numbers associated with the brick-and-mortar stores makes the most sense to me," Clark said. "USDA is treating the websites as stand-alone businesses, and I cannot imagine retailers are treating their online business the same way. Instead online is just an expansion of our current business."

According to a USDA spokesperson, most of the retailers looking to offer SNAP online purchasing already have SNAP authorizations for their brick-and-mortar stores.

"From an operational standpoint, a separate SNAP authorization allows online transactions to be validated and approved. A retailer’s online SNAP presence can involve none, one, many, all, or a select subset of brick-and-mortar locations," the spokesperson wrote in an email. "From an oversight standpoint, it is critical that FNS have a view into how online orders will be fulfilled. As this area continues to evolve, FNS will consider opportunities for streamlining the authorization process."

Currently, Fiserv is the only payment processing company approved as a partner with the USDA, but Goad said he anticipates there will be other technologies in the future.

A USDA spokesperson wrote in an email that "FNS is also providing technical assistance to 15 e-commerce providers to further ease the process of becoming an approved online retailer." In addition, FNS said in November that it's working to partner with another company that can also provide a secure PIN entry, which would increase capacity.

Cost can be a concern for technology vendors, but their expenses often stem from creating expertise internally and investing in software developers to build out the e-commerce capabilities of SNAP online purchasing.

For independent grocers, the costs associated with the pilot and offering e-commerce can be a barrier. “Due to the minimum fees by Fiserv, we are required to do a certain amount of EBT online business for it to be worthwhile, so we are hopeful that we have the swing [financially] that we need,” Clark said.

Goad declined to share specific numbers on pricing and instead commented broadly on the fee structure, saying that there can be tiers for the costs, "but that everybody starts off with the same initial pricing." A spokesperson for Fiserv confirmed that the costs include an initial setup fee, a monthly fee and a gateway fee.

Another concern is the required testing of EBT online transactions.

FNS' testing checks to make sure the retailer's e-commerce site, the secure PIN pad and the payment processing work according to USDA requirements, a USDA spokesperson said. "Typically this will be once per banner, unless one banner employs various websites or payment processing options," the spokesperson wrote. "At this early juncture, each retailer's implementation of online purchasing is unique and therefore no one-size-fits-all approach works for the various solutions."

The USDA spokesperson admitted the agency has run into issues during the testing process that have to be corrected, and those problems "may or may not be attributed to the e-commerce platform."

Testing was the most time-consuming part of the process for Carlie C’s IGA, owner Mack McLamb said, noting the store went through testing once for the banner. There were "hundreds" of different testing scenarios the EBT online payment system had to go through, from seeing what happened when customers wanted to refund purchases to customers taking items out of the digital shopping cart, McLamb said.

"They have all of these different types of scenarios that they test — 'When I do this, what takes place? How does it work?' — that kind of thing," McLamb said. "They're trying to get the experience to the customer to be as smooth and quick and as reasonable, in their mind, as they can be."

Brian Moyer, CEO of Freshop, described the testing as a "heavy lift" that he wants to see shifted from the grocers more onto the technology vendors. "Once we get tested and certified in a state — each state does have different ways of doing things — then each subsequent retailer should be able to benefit from that, which, of course, would reduce any costs," he said.

The NGA last year pointed to testing of each individual store location as one of the key deterrents to independent grocers joining the pilot. FNS confirmed last month that testing "does not need to happen at each store location," Pfaffenroth said. The USDA spokesperson, however, said testing was never required for each storefront in each state. The conflicting information highlights the complexity of the rollout, as well as some larger communication issues.

There are some headaches, though, that for now can’t be avoided. For example, grocers and vendors have their hands tied when it comes to the technological challenges of making sure that sales tax is only calculated for non-SNAP items.

There's also the required digital PIN pad that EBT shoppers use for online orders that tech vendors are worried will confuse consumers because it randomizes how numbers appear on the keypad. Each time a user enters a single number, the numbers scramble on the keypad — an element aimed at protecting the user’s PIN.

A push for more resources

Wading through federal and state requirements can be a challenge for grocers and tech vendors. To help, the Food Industry Association debuted a digital feeding assistance toolkit last spring. The NGA is working on a toolkit for its members on best practices and is hosting retail-focused webinars with Fiserv on SNAP online purchasing, Pfaffenroth said.

The NGA has been vocal with suggestions for how to knock down barriers that grocers still face with offering SNAP online purchasing. "NGA was able to secure $1 million in funding for FNS to implement SNAP online purchasing and technical assistance in the end-of-year COVID-19 stimulus bill," Pfaffenroth said, adding that the trade group would like to see Congress provide FNS with more resources.

The $1 million allotment was a part of the COVID-19 stimulus Congress passed in December that set aside $5 million for SNAP online purchasing, which includes boosting efforts to add farmers markets and improving security with mobile payment technology.

Federal assistance to help smaller grocers offer SNAP online purchasing is one of the top legislative priorities that NGA President and CEO Greg Ferrara outlined in a Jan. 20 letter to President Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris.

Legislation introduced last week in Congress would set aside funding for a center housed under the USDA to help small retailers with technical assistance when trying to launch SNAP online purchasing. It also would create a universal, app-based portal giving shoppers access to the SNAP retailers.

Associations on the state level are also pushing for more resources to help small grocers. The Maine Grocers & Food Producers Association, for example, is asking its U.S. senators about getting more "technical assistance and programing development funding directly to the storefronts," Christine Cummings, the association’s executive director, wrote in an email. On the state level, the association is looking into partnerships with e-commerce platform providers, Cummings said.

Solving the challenges small grocers face with SNAP online purchasing is important because they can often more easily reach SNAP participants by having stronger community ties and can potentially offer lower prices.

"Many of our small grocers were starting to explore selling online pre-pandemic, [but] didn't necessarily have the technology in place," Cummings said, noting that rising healthcare costs, the state’s $12.15 minimum wage and the costs implementing COVID-19 safety measures have created financial challenges.

When Maine goes live with the pilot, Amazon and Walmart are already authorized for the state, a USDA spokesperson said.

As for the remaining states and territories, Alaska, Guam, Louisiana, Montana and the U.S. Virgin Islands are not currently participating in the SNAP online purchasing pilot, but Louisiana and Montana are working to be a part of it, according to a USDA spokesperson.

The accessibility problem

E-commerce can be a game-changer for reaching SNAP recipients who are part of vulnerable communities, including seniors; people with disabilities or have mobility challenges; those at a higher risk of severe complications from COVID-19; or people who live far away from a brick-and-mortar grocery store.

"To me, the question isn't, 'Where is it approved to theoretically happen?' The question is, 'How many people are able to use it?'"

Joel Berg

CEO, Hunger Free America

Joel LaFrance, vice president of product at Basketful, a grocery e-commerce platform, said that it's also an effective way to combat rising food insecurity. "Access to SNAP dollars is not enough," LaFrance said. "Sixty-five percent of [SNAP recipients] have low access to groceries, and online grocery can be a tool to fill in that gap."

Home grocery delivery reaches 86% of the U.S. population through more than 50 retailers that Basketful tracks, the company shared in a blog post last spring: "That delivery coverage, as of April [2020], has the ability to shrink the 49% of Americans with low access [to groceries] to 3%."

Online grocery delivery helps to reach low access communities

Z

A

But some researchers are skeptical about how much online SNAP programs can fully address food insecurity. Eric Brandt, clinical lecturer at the University of Michigan who researches nutrition policy impacts on health, said he views SNAP online purchasing as a small — but important — piece to solving food insecurity by expanding both access to groceries and "quality" items. "I think SNAP online could be a gateway to potentially both of those things," Brandt said. "As it stands alone, it doesn’t completely solve all the problems."

Craig Gundersen, a University of Illinois professor who focuses on SNAP, said SNAP online payments aren’t likely to make much of a dent in solving food insecurity or in reaching the majority of SNAP recipients. Gundersen predicts that about 5% to 10% of SNAP recipients will turn to online shopping.

The usual pitfalls plaguing e-commerce become even bigger obstacles for SNAP participants, from quality concerns with picking fresh produce to increased costs, Gundersen said.

Additional expenses vary from retailer to retailer for online ordering and common ones include delivery and pickup fees, differences in pricing between in-store and online items and a temporary "buffer" charge that requires a payment method separate from the EBT card to cover any changes in the order total between when the order is placed and when it is picked.

For SNAP recipients who are impoverished, underbanked or unbanked, those expenses can be prohibitive. A "vast majority" of SNAP recipients are impoverished and account for more than 90% of all SNAP benefits, according to a post analyzing USDA data from fiscal year 2018 by the Peter G. Peterson Foundation, which focuses on fiscal barriers in the U.S.

To effectively address food insecurity, Gundersen says the government needs to permanently increase the benefit level by roughly 20% and expand the eligibility threshold for SNAP. For the grocery industry to combat hunger, offering low prices both in-store and online is key because "it makes the SNAP dollar stretch a lot farther," Gundersen said.

As the pandemic continues, sources say offering and expanding delivery is especially important to shoppers looking to avoid in-person shopping due to health and safety concerns. But limited geographic reach and fees can post barriers.

Grocery e-commerce and delivery are widely available to SNAP households within urban food deserts, but they are rarely available in rural ones, according to research published in 2019 by Yale University, which looked at grocery delivery accessibility in eight of the states participating in the USDA's SNAP online purchasing pilot. Brandt, one of the researchers behind the study, said he expects those results to be similar today, but that more people would be covered by grocery delivery as time goes on.

Because delivery fees aren’t covered under SNAP benefits, shoppers usually have to use another payment method. "They might only have cash and EBT," Brandt said. "You can't really pay with cash to pay for delivery fees, so it might limit some of the most socially, economically marginalized individuals in society from being able to participate."

Even with the financial issues surrounding delivery, offering the service can be vital in reaching people with mobility challenges.

"I think the real holy grail is combining online ordering with home delivery, and if not home delivery, one thing I'm pushing the federal government and others to consider is hub delivery," which would involve grocers dropping off delivery orders at easily accessible community locations, said Joel Berg, CEO of the anti-hunger and anti-poverty organization Hunger Free America.

Grocers that don't have delivery or offer it with a limited range are opening themselves up to competition. For Cameron Market, delivery is "our competitive advantage to Walmart," Clark said. "Transportation can be a real area of need for some EBT customers, and we are happy to offer this service for our customers," he said.

Ultimately as SNAP online purchasing becomes more widely available, sources said the main question going forward is how accessible it will become.

"To me, the question isn't, ‘Where is it approved to theoretically happen?' The question is, 'How many people are able to use it?'" Berg said.

The Online SNAP series is brought to you by Mercatus, a recognized leader in grocery eCommerce technology. To learn more about their SNAP EBT Online solution and access resources, visit their website here. Mercatus has no influence over Grocery Dive's coverage within the articles, and content does not reflect the views or opinions of Mercatus or its employees.