Kroger’s announcement on Tuesday that it will shutter three of its robotic e-commerce fulfillment facilities represents a sharp turnabout for the grocery company, which until recently had expressed confidence in its ability to leverage automation to run a profitable online grocery business.

Less than a year ago, Kroger said it planned to expand the fleet of high-tech fulfillment centers it has been developing in partnership with U.K.-based warehouse automation company Ocado. And in mid-2024, Kroger revealed that it would install new technology from Ocado to improve the efficiency of the warehouses.

When Kroger launched its partnership with Ocado, the company “believed in the relentless drive to innovate way ahead of the market in order to delight our customers and advance our position as one of America’s leading e-commerce companies,” former Kroger CEO Rodney McMullen said in a video about improvements to its equipment that the automation company announced last year.

However, Kroger’s projected confidence came even as it was questioning whether the Ocado network was living up to expectations.

Kroger revealed in September 2023 that it had decided to pause development of the Ocado project as it waited to see if sites it had already started operating would meet performance benchmarks.

In a further sign that its strategy was faltering, Kroger announced last March it would close three spoke facilities that worked in tandem with several of its robotic centers, with a spokesperson noting that the facilities “did not meet the benchmarks we set for success.”

By September 2025, it was clear that depending on automation as the foundation of a money-making grocery delivery business was probably not going to pan out for Kroger. Speaking during an earnings call, interim Kroger CEO Ron Sargent — who took over in March after McMullen’s sudden departure following an ethics probe — said the company would conduct a “full site-by-site analysis” of the Ocado network.

Sargent also said Kroger would refocus its e-commerce efforts on its fleet of more than 2,700 grocery supermarkets because it believed that its stores gave it a way to “reach new customer segments and expand rapid delivery capabilities without significant capital investments.”

Kroger said on Tuesday that its decision to close the three robotic facilities, along with other adjustments to its e-commerce operations, would provide a $400 million boost as it looks to improve e-commerce profitability. But the course-correction will be expensive, forcing Kroger to incur charges of about $2.6 billion.

Ken Fenyo, a former Kroger executive who now advises retailers on technology as managing partner of Pine Street Advisors, said the changes Kroger is making reflect the broader reality that grocery e-commerce has not reached the levels the industry had predicted when the COVID-19 pandemic supercharged digital sales five years ago.

Fenyo added that Kroger’s decision to locate the Ocado centers outside of cities turned out to be a key flaw.

“Ultimately those were hard places to make this model work,” said Fenyo. “You didn’t have enough people ordering, and you had a fair amount of distance to drive to get the orders to them. And so ultimately, these large centers were just not processing enough orders to pay for all that technology investment you had to make.”

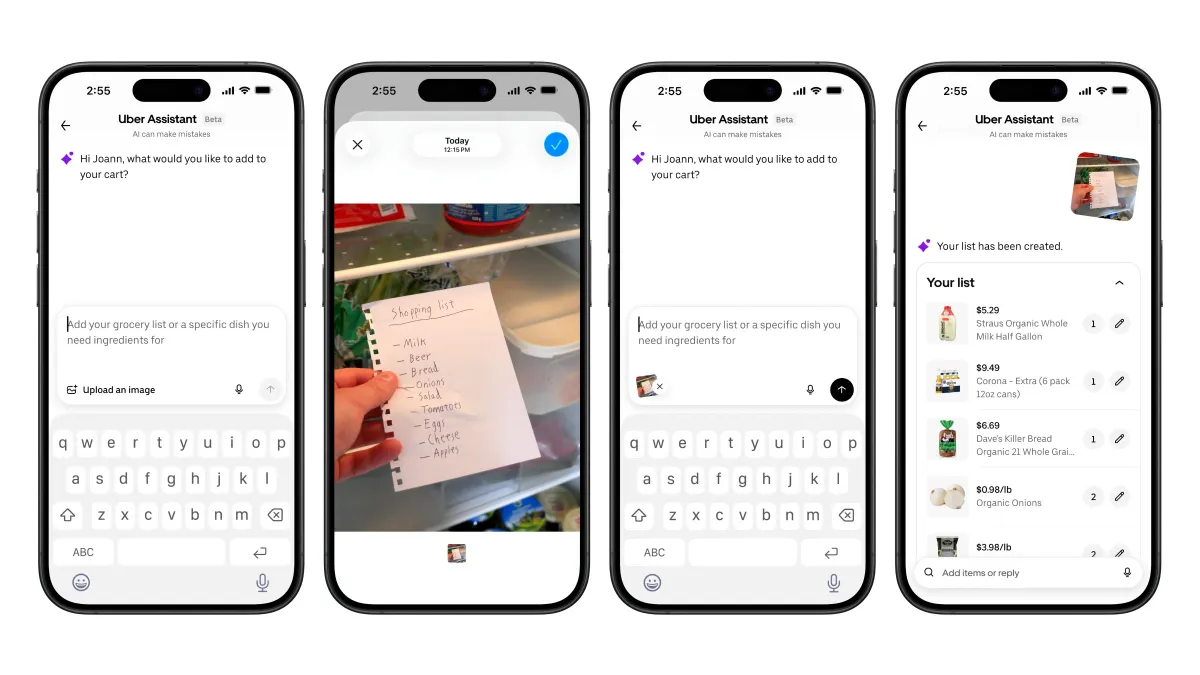

With its automated fulfillment network, Kroger bet that consumers would be willing to trade delivery speed for sensible prices on grocery orders. That model has been highly successful for Ocado in the U.K., but U.S. consumers have shown they value speed of delivery, with companies like Instacart and DoorDash expanding rapidly in recent years and rolling out services like 30-minute delivery.

Acknowledging this reality, Kroger noted on Tuesday that it’s deepening partnerships with third-party delivery companies. The grocer also said it will pilot “capital-light, store-based automation in high-volume markets” — a seeming nod to the type of micro-fulfillment technology that grocers have tested in recent years, and that Amazon is currently piloting in a Whole Foods Market store in Pennsylvania.

Fenyo pointed out that micro-fulfillment technology has also run into significant headwinds, adding that he thinks that outside of areas with large numbers of shoppers and high online ordering volume, putting automated order-assembly systems in stores probably doesn’t justify the cost.

Kroger’s decision to reduce its commitment to automation also poses a significant setback to Ocado, which has positioned its relationship with Kroger as a key endorsement of its warehouse automation technology. Shares in the U.K.-based robotics company have fallen dramatically and are now back to their level 15 years ago, when the company went public.